AMERICAN FINE ARTS - IF CULTURE MEANS ANYTHING

curated by James Fuentes, essay by Jackie McAllister

Colin

De Land (1955-2003)

Jackie McAllister, August 2003

“I've thought for a long time that Colin de Land, as an art dealer,

is historically-significant on the order of, and as commensurate in effect

to, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979) and Leo Castelli without followers,

in the sense that his steadfast cross-examination and engagement with

all the elements operating within his chosen vocational field, is not

easily replicable by formula. Colin so assiduously audited the conceptual

and formal processes operative within the social space of the art world,

as well as the agents contributing to the production, display, and circulation

of art works, in tandem with the quotidian practice of running a commercial

art gallery, that it is hard to conceive of any duplication of his effort.

By 1989 I had been Researcher in Contemporary Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum

for a couple of years, and had spent a year in New York attending the

Whitney Independent Study Program. I have developed a quasi-anthropological

interest in finding-out how commercial galleries operated, and was looking

for a job. At the end of a job interview with Larry Shopmaker, then Director

of the Max Protetch Gallery at 568 Broadway, he said that while he would

happily hire me, he thought I would most likely become bored within three

months, and so suggested that I keep looking. He let me know that if nothing

turned-up he would still give me a job. His fortuitous redirection eventually

led me to some place very different from any conventional set-up encountered

in most galleries.

Emboldened by this encouragement, I next had a talk with Mark Dion (at

that time he was not yet represented by the gallery), who suggested that

I go and talk to Colin de Land at American Fine Arts, Co., found then

at 40 Wooster Street. A previous visit to the gallery was when I first

encountered an exhibition by Cady Noland - whose work exemplified the

developed conceptual approach Colin was then beginning to implement at

the gallery.

Anyway, the following Saturday I went to an opening at A.F.A., Co., took

a quick look at the show, fished-out a “pony” bottle of Budweiser

from the ice-filled trash next to the plywood front desk (built by Erik

Oppenheim), then headed to the back office area. Stepping into the back

office, I saw Colin down on one knee, dressed in a blue pin-striped suit,

making a solo attempt to bubble-wrap a Jessica Stockholder “Christmas

Tree” piece (“Kissing the Wall”?), all the while juggling

a cigarette and cordless phone. “Hi, Colin,” “Hey, Jackie,”

exchanging greetings, “what's up with you?,” “Not much…,”

and then, “looking for a job.” “Oh yeah? Come back and

see me on Tuesday, I want to talk to you.”

Up until Tuesday noontime, I worked out all the “improvements and

strategies” that I had to offer to the gallery, and duly at the “interview”

I laid out all my ambitious plans, to which Colin after listening with

some bemusement, said “Well, that's certainly an impassioned speech.

When can you start?” “Beginning of next week?” “How

about now?” I think that should have dispelled my delusions, should

have told me that things would be going by Colin's routine, not mine,

ha ha.

For two years and two months, I worked at 40 Wooster, with Kavin Buck,

Huw Chadbourn, Angela Cumberbirch, Regina Moller, and Mimi Wheeler. This

was an intensely busy time for the gallery: for example, Cady Noland (C.N.),

then represented by A.F.A., Co., was included in all the major exhibitions

of 1990: “Documenta”, Kassel; the “Venice Biennal”;

the “Whitney Biennial”; a large sculpture exhibition in Berlin:

“Metropolis” curated by Christos Joachimides and Norman Rosenthal;

and an exhibition at the Luring Augustine Hetzler space in Santa Monica.

Jessica Diamond and Jessica Stockholder were also selected for the “Whitney

Biennial” that year. Other gallery artists at that time included:

Nancy Barton, Charles Clough, Mark Dion, Daniel Faust, Peter Fend, Andrea

Fraser, Peter Hopkins, Thom Merrick, Aimee Morgana, Sam Samore, Peter

Santino, Jon Tower, and Julia Wachtel. At the time I left, to curate exhibitions

and organize public projects at Real Art Ways in Hartford, Connecticut,

artists like Art Club 2000, Dennis Balk, and Tom Burr were starting to

show with the gallery. Colin's spirit of continual renewal could always

be seen in the new faces around him, whether they were new artists or

people working at the gallery.

Early on in my employment, I watched as Colin and Thom Merrick installed

an exhibition of Thom's new sculpture. When they had finished installing

four pieces, I seem to remember: two wall pieces, two floor pieces, Colin

asked Thom if he was happy with the installation, which Thom was. Thereupon

Colin asked how he would feel if one piece was relocated to the back office

area. Thom reluctantly agreed and when the piece was removed there was

a definite sense that your appetite had been whetted, that you wanted

to see more, and the work in back did seem to be a nice fill-up that completed

the experience. Colin could drive artists to distraction by taking almost

the entire installation week to consider the installation before installing

the pieces, this was an interval of concentration and deliberation when

all the exhibiting options available were to be explored with the works

in the gallery. During this period, I became aware that Colin would make

a point of ritualistically touching every object there to be installed.

Working at the front desk of A.F.A., Co., I met literally thousands of

people: artists, critics, curators, dealers (Pat Hearn, of course; and

Christian Nagel has always been a great friend and ally of the gallery),

etc., each of whom seemed to have their own particular relationship with

Colin. He could give each person coming into contact with him the very

real sense that he was responding, not in some generalized, conventional

manner, but within the terms of that discrete relationship existing between

yourself and Colin. A little reminiscence: I was privy to an exchange

in the basement between Martin Kippenberger and “Uncle Colin”

during which M.K., holding under each of his outstretched arms a black-and-white

photograph by Peter Hopkins of dump areas found on high-way embankments,

jocularly asked, “Which one should I buy? This garbage, or that garbage?”

It was also then that I fell in love with my future girlfriend, the artist

Diana Balton, who was then collaborating on a project with C.N. (Sitting

on the steps outside the gallery, Colin once gave me advice about my love

life, but that's another story…)

During this time, a Business student from New Jersey, Christine Tsvetanov,

working on her MBA thesis examining how a small business operates in the

art market, started a summer internship at American Fine Arts, Co. When

she turned up for her interview with C.d.L., in mini-skirt and high-heels,

I was very skeptical, “This won't last a week,” I thought. Of

course, I was very much mistaken, as was often the case when one tried

to second-guess Colin, and now, thirteen years later and counting, Christine

with Daniel McDonald are the ones to whom Colin “vouchsafed”

the future course of the gallery. In addition, Lizzi Bougatsos, Taka Imamura,

and Rosalie Knox, should be mentioned for their ongoing service to the

gallery.

The most important lesson to be learned from Colin was his idea about

what could be exhibited at a gallery. The key to his approach can be found

in the proper name of the gallery: American Fine Arts, Co. For Colin,

who had an abiding interest in linguistics, each of the lexical items

selected from a vertical paradigmatic menu: “American,” “Fine,”

“Arts,” and “Co.” are combined syntactically to form

a meaningful classification which is arrayed in a horizontal dimension.

What is that which is described by these particular words aligned in this

precise order: American Fine Arts, Co.? By his example, we now know that,

that far from being a limitation, “American Fine Arts, Co.”

is a category under whose heading a whole host of people can interact

and a tremendous range of activities can come into play.

Colin's approach, unlike so many gallerists, was not based in an “advocative”

stance. That is, where the gallery, and its representatives, working with

the mechanics of display and publicity, play the role of an “advocate”

in promoting the value of the work for sale, and work to further the artist's

career. While the viewer is implicitly, or explicitly, limited to making

a, primarily, aesthetic-based judgment in response to an exemplar of the

“best” work as determined, or available, to the gallery. Rather,

when entering American Fine Arts, Co., the viewer is invited to engage

any number of effects pertaining to questions of meaning/production. For

this reason, many artists did not quite understand why Colin was not per

se interested in “career management.” This was not the primary

purpose of the gallery: those artists who tended to look after their own

careers were the ones who fared best when represented by American Fine

Arts, Co.

Likewise, I had been querying Colin about his advertising strategy, mailing

list, public relations, etc., and asked him why the gallery did not produce

press releases, and he explained that there was a very small window of

time in which the visual work of art is experienced before this perception

is inevitably shaped by language, and this window should be kept open

as long as possible: that we should resist prematurely foreclosing the

meaning derived from the visual, resisting as long as possible channeling

the viewer's experience through the strictures of language. There exists

relatively few texts as written by Colin de Land, I remember him agonizing

over a piece of Roman Signer, published in Parkett Magazine, it'd be good

to go back and look at that. For a time he even resisted committing price

lists to paper, preferring to keep them in his head, making it necessary

that he be consulted before any sale was 'closed.'

One time Colin was out of the gallery, probably having a coffee and meeting

around the corner, during an installation week, and I typed up on a gallery

card, the following: Closed for Installation. I taped it to the front

door. Colin came back and took down the card and handed it to me and said

“We never use that word.” “Which word?,” I asked.

And he said, “Closed,” continuing: “We never use that word,

'Closed,' in connection to the gallery.” This open-door policy often

leads to people sticking their head in the door and wondering if the gallery

is in the middle of installation. Also, people were free to wander into

the back office and engage Colin in conversation. He was always happy

to hear some piece of news first, and would often mentally store away

bits of information and then months later, in a very generous, open way,

introduce two people with shared interests, or who could benefit to meet

each other, and who might not otherwise meet. To reduce some of the distractions

Colin had a habit of conducting some of his more sensitive one-on-one

meetings around the corner, over coffee and cigarettes, at cafes like

Novecento on West Broadway.

Things were not always rosy working with C.d.L., my admitted pedantry

and his exasperating inscrutability could certainly rub each other the

wrong way, and sometimes we had our spats (I'm sometimes amazed, looking

back, at his tolerant attitude, how he looked out for me, I know I certainly

tried his patience back then.) After some disagreement, Angie Cumberbirch

explained to me that Colin and I could only become real friends after

I stopped working for him. And sometimes he would let you know how sensitive

he was to your perception of him; it was touching how much he could be

pricked by the smallest perceived slight. Years later, outside the Whitney

Museum, attending an artist's talk given by Gareth James (who arranged

to “close the gallery during wRECONSTRUCTION, curated by Storm Van

Helsing in 2001), I went over to Colin to say “Hi,” and he turned

to his companion, Kembra Pfahler, and introduced me by saying, “Kembra,

I'd like you to meet an old friend of mine.” This made me extremely

proud.”

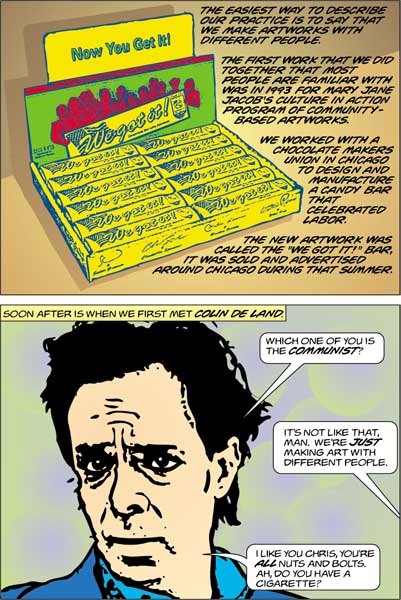

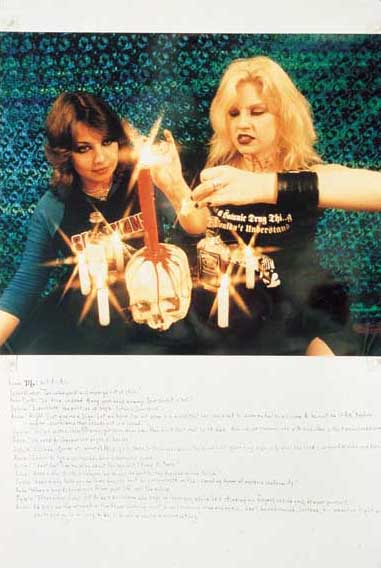

Greenmann & Sperandio from Fantastic Sh*t at American Fine Arts, New York 1996

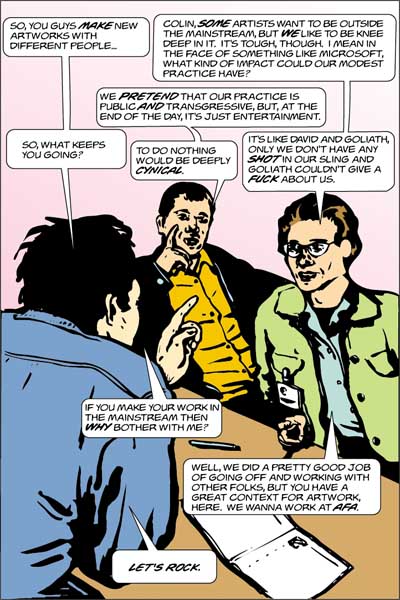

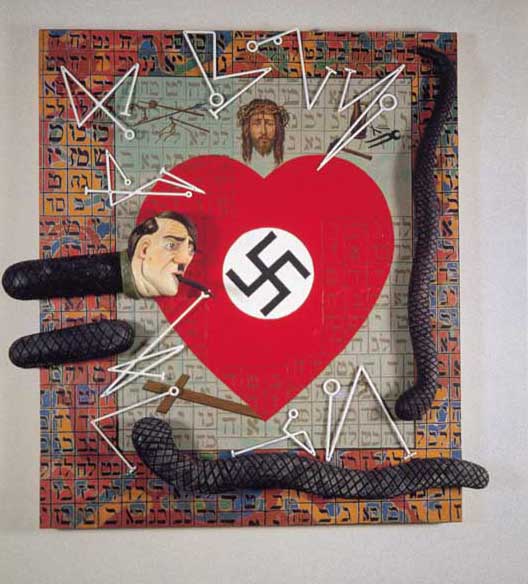

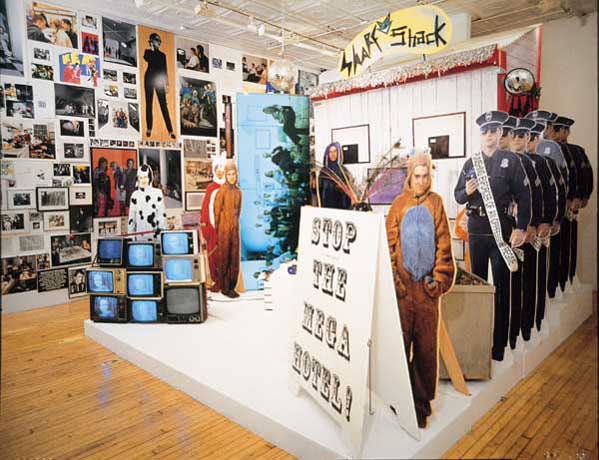

wRECONSTRUCTION Curated by Storm

Van Helsing, American Fine Arts, Co., New York 2001

“Just because you can, doesn't mean you should.”

“Whether you're a spiritualist engaging in some kind of mental tantric

sex or a dialectitian, our freedom exists largely in the power to choose

something other than that to which we're fated […] What's shocking

is not that painting, sculpture, photography and video are the only kinds

of exhibitions now, but the degree to which they contribute to the suppression

of other possibilities.” from an interview with Tim Griffin, Time

Out New York

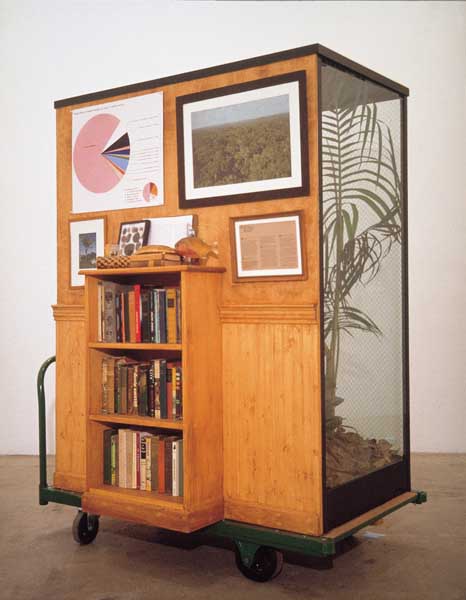

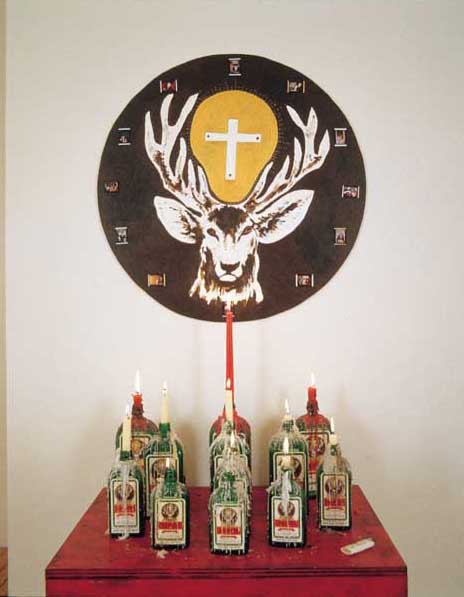

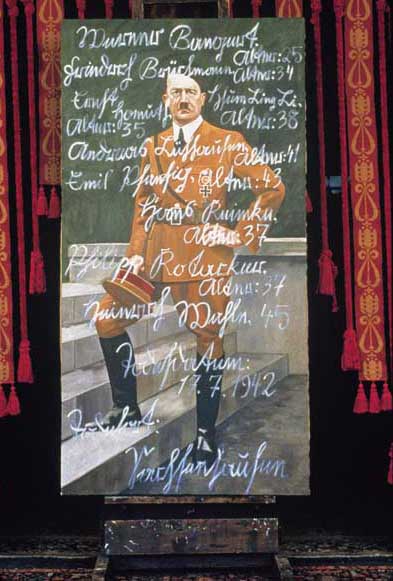

Stephan Dillemuth, A Coal By Any Other

Name, American Fine Arts, Co., New York 2002

“In each of its rooms, American Fine Arts plays host to one of the

four important stages of an artists life-the art school, the studio, the

gallery, and the museum. On each of these stages, the art object plays

a dual role, as an essence in and of themselves, and as a spiritual stage

device.” quote by Colin de Land from the exhibition press release

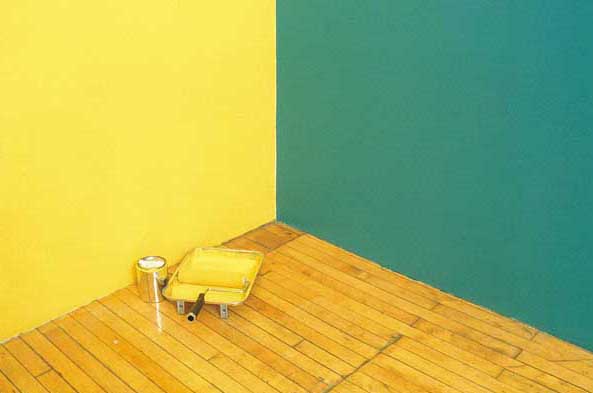

Mark Dion & William Schefferine, Tropical Rain Forest Preserves (1989, remade 2003) from Mark Dion with William Schefferine, American Fine Arts, Co., New York 1990

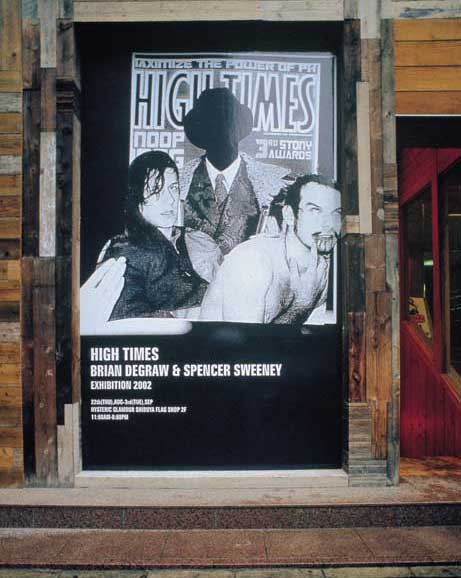

Exhibition announcement outside of Hysteric Glamour, Tokyo 2002

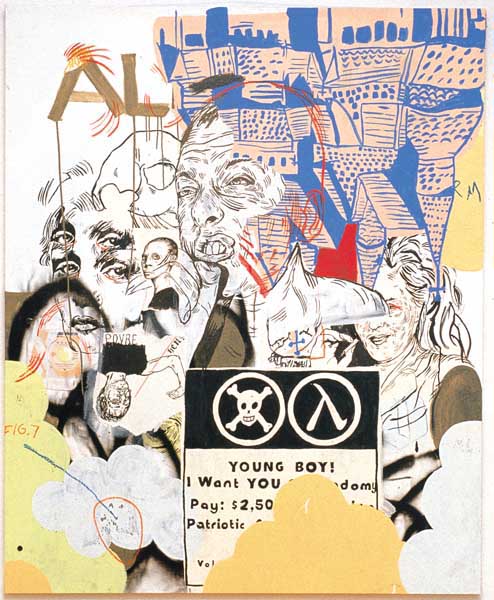

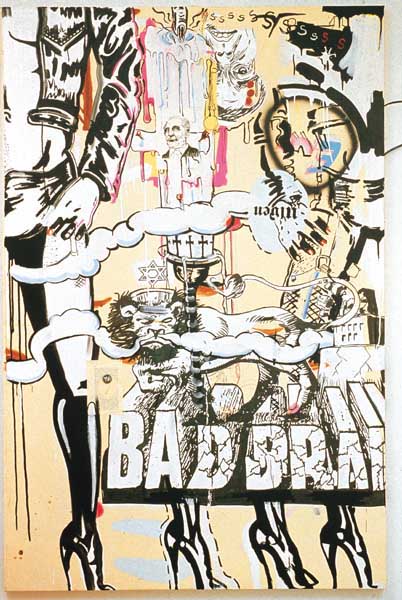

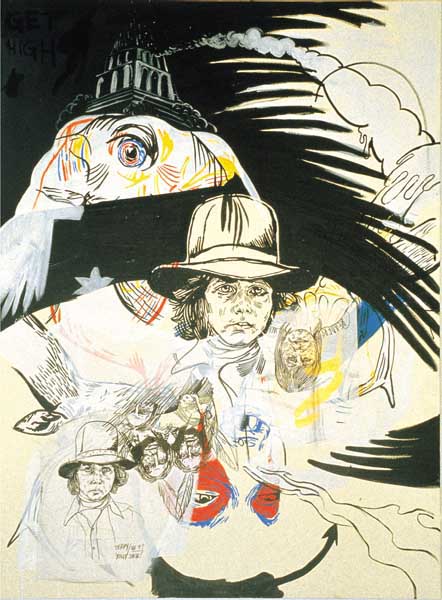

Brian DeGraw & Spencer Sweeney, untiteled collaborative paintings, American Fine Arts, New York2002

Collaborative paintings produced for Hysteric Glamour, Tokyo 2002

Exhibition announcement outside of Hysteric Glamour, Tokyo 2002

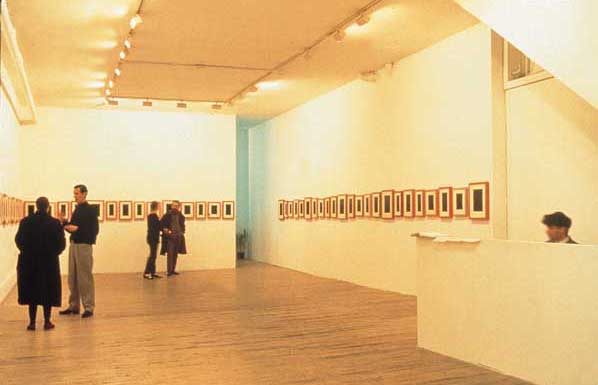

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights:

A Gallery Talk, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia 1989

Andrea Fraser with Allan McCollum, May I Help You?, American Fine

Arts, Co., New York 1991

Andrea Fraser, Please ask for assistance, American Fine Arts, Co.,

New York 1993

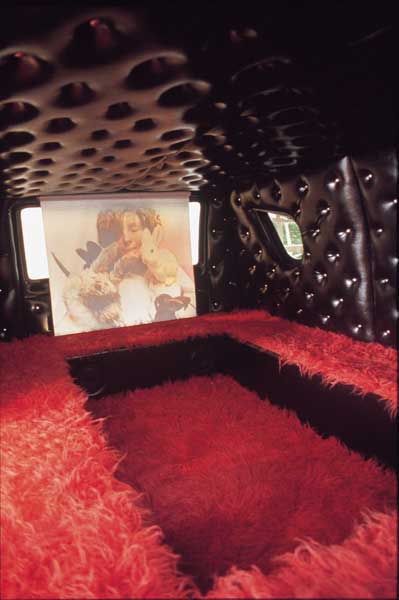

Alex Bag

Installation view, American Fine Arts, Co., New York 2000

“Mobile Video Viewing Unit” Installation view

Installation view, American Fine Arts, Co. at P.H.A.G., New York 2000

McDermott & McGough, The Lust that Comes from Nothing, American Fine Arts, New York, 2002

Frank Schroder, Crowd of Women 1909-1959,

American Fine Arts, Co., New York 1998

“An on going collection of 150 plus portraits of women from 1909-1959...

Collected over the last 7-10 years, the former painter has transferred

the struggle of painting, to authoring this history of rejected struggles,

and rejected subjects. Pruned from the unsensationalized ground of middle

culture, the portraits were chosen for their unglamourized factographic

qualities, as well as painterly competence.” quote by Colin de Land,

from the exhibition press release

The following four pages feature four projects produced by Art Club 2000/AC2K (Craig Wadlin, Shannon Pultz, Soibian Spring, Daniel McDonald, Gillian Haratani, Patterson Beckwith and Sarah Rossiter.) In order of appearance: SoHo So Long, Commingle, 1970, and 1999.

In 1996 AC2K conducted interviews with art critics, curators and gallerists

regarding the “shift” from Soho to Chelsea which culminated

as a 300 page photocopied book called SoHo So Long. At the time

there were only six galleries in Chelsea, but the economic prosperity

of the mid-late nineties hadn't yet kicked in, and the subsequent mass

migration could not be foreseen. The following material is relevant in

its observations on how galleries transform neighborhoods and an insiders

perspective on how the critics, dealers and collectors dealt with two

central questions, “Is SoHo over?” and, “Is Chelsea the

new frontier?” Here are some excerpts from the limited edition book,

keep in mind it was compiled in July of 1996.

AC2K: What do you think of the shift from SoHo to Chelsea?

Francesco Bonami: SoHo to Chelsea. It belongs to the American tradition

of nomadic people. You move from one place to another trying to find the

right one, to settle down. It's an endless process.

AC2K: Do you enjoy going to Chelsea to look at art?

Joshua Decter: Again, to be blunt, I am waiting for the day when I hear

agnes b. moves up there, or Commes des Garcons, because that would be

adequate enticement for me to be in that area. Because, as you know, I'm

such a fashion slave and I've such a nose for fashion, that I follow boutiques.

I would suggest that 303 and Metro Pictures, Pat or Matthew, discuss the

possibilities with Commes de Garcons, agnes b., Betsy Johnson or Armani.

If they installed boutiques up there, that would get a lot more people

up there, including myself… At this point, I probably enjoy going

to Chelsea more than SoHo. I find SoHo to be, particularly on weekends,

a rather untenable, odious experience. It's overcrowded. It reminds me

of Easthampton on July 4th weekend and I can't think of anything more

odious than that.

AC2K: Why did you decide to move to SoHo?

Barbara Gladstone: In 1983, I felt that the real life of art was downtown.

I did not like being in a big building where people had to go up in an

elevator. I felt that it wasn't a real neighborhood, and I felt that art

isn't a business in the sense that other things are a business, and that

it should be different to go to an art gallery than to your accountant's

office.

AC2K: Do you think that Chelsea will change a lot, now that there are

galleries moving up there?

Marvin Kosmin: I think it will have to. I think that simply because galleries

have bought property, it sort of insures the fact that they'll be there.

And if they're there, I think that a lot of other places will open there.

AC2K: What do you think of the shift to Chelsea?

James Meyer: I just see it as the latest in a series of movements of the

art world through the past century. In the 1940's it was Greenwich Vilage

and that dated back to the teens, then there was the shift to the East

Village in the 1950's (eight street), and in the late 60's galleries started

moving to SoHo. Then there was a return to the East Village in the 80's,

followed by another return to SoHo. And now Chelsea. I see Paula Cooper's

departure particularly, as emblematic of SoHo's end. She was SoHo's original

gallery pioneer. I don't see this exodus as a bad thing: it's something

normal, a process whereby artists and galleries just move, because the

prior place has taken on material and symbolic implications which they

don't like. In moving to another place there's this hope that a new kind

of identity for art, and those involved with art, can be put out there.

AC2K: Are you saying that if Chelsea became as heavily trafficked a neighborhood

for art that you would consider moving there?

Freidrich Petzel: Yeah you see, I'm not nostalgic about anything. If SoHo

doesn't work, I'd be, boom, the first one out of there. I could care less.

It works now for the artists really well. And if I have the slightest

feeling that it doesn't anymore, I'd be the first one out of here. So

it's not so much for me the neighborhood, as to create a certain forum

to look at art, and as soon as that doesn't do the trick anymore, out.

AC2K: So you enjoy going there (Chelsea)?

Javid Jerrard Rimanelli: I hate Chelsea. I think it's just an avatar of

moral, psychological or esthetic spiritual degradation. The defile of

8th Avenue, I find, defiles me. But as I'm… you know… various

nomadic… you know… blow up dirigible's of humanity pass by me

in various indecourous outfits. But it is convenient. So that's how I

feel about Chelsea, I loathe it, but I don't mind it.*

(*from SoHo So Long, 1996)

In our exhibition, Commingle, Art Club 2000 focused on an investigation

of The Gap. In many of our group photos we wear matching costumes which

were generously supplied to us by The Gap's “no-hassle” return

policy. After a long day of photo shoots throughout Manhattan, one lucky

group member would bring back seven matching, sweaty Gap ensembles with

the simple explanation, “I decided I didn't like these anymore”.

The Gap was less accommodating when we attempted to do some reconnaissance

photography of their merchandising techniques, architectural detailing,

and dressing rooms. On one occasion and Art Club member was physically

pushed out of the store by a security guard while other group members

ran for their lives.

As our relationship with The Gap continued, we began to feel the need

for a closer look into the inner working of this institution. Several

Art Club 2000 members applied for jobs at local branches. The Gap didn't

even send us the customary “no thank you” letters.

In our frustration, we decided to look through The Gap's trash. The first

night, at The Gap on St. Mark's Place in New York's trendy East Village,

we found innumerable inter-office memos, employee evaluation forms, job

applications, the telephone numbers of all the employees, a pair of old

Gap jeans, and sixteen dollars in cash. This fuled an intensive search

over the next three weeks which involved going to almost every Gap, Baby

Gap, Gap Kids, and Gap Shoes located in Manhattan. Missions were conducted

between midnight and 3:00 am in a pick-up truck with some members sorting

through garbage on location, while others catalogued and organized the

materials in the back of the truck, according to store location and date

found.

The materials collected in these expeditions were a vital source of information in the production of our exhibition, and gave us all a greater insight into the inner workings of this megalopic corporation. Amongst endless stacks of paperwork and packing materials, (which The Gap apparently does not recycle) we found: a Babar rattle, a William Gibson novel, two unopened letters from The Gay Men’s Health Crisis, inter-office memos discussing suspicious phone calls, The Gap loss-prevention handbook, employee payroll charts, broken hangers, countless shoe boxes, panty hose, broken anti-theft devices, even a dirty diaper. By looking at the trash, we learned the meaning of the “G.A.P. A.C.T.”, the dangers of getting bogged down in tasks, the methods used to prevent employee theft (which include managers checking for garments in the trash before it’s dumped), what it means to prevent store “shrinkage,” and why the fitting room is a great place to sell. This information practically constitutes its own language, which all The Gap employees use to communicate.

Much of this kind of significant garbage has yet to be thoroughly examined, and the thought that every Gap in every state is producing more and more of it every day boggles the garbologist’s investigative mind. The information in all those clear bags holds the promise of filling in all the gaps in our understanding of the store that’s becoming a bigger and bigger part of all our lives. Coming to a convenient corner location nearer to you than you think, The Gap.

Intrigued by Art Club 2000’s obsession, we asked one of the group’s members, Daniel McDonald, what was up.

Daniel: We found this one thing that managers write to the next shift of managers. You have to write what happened that day. And there was like this piece of paper with “Gap Rap” on the top of it. One of the managers had written down who had come in that day who was famous. And it said, “Larry Fishbone,” and then they’d crossed out “bone” and written, “burne.” Plus it said, “Regis Philbin and wife” and what they had bought.

Grand Royal: What store was this?

D: I think this was the store on St. Mark’s.

GR: Wow, Regis Philbin on St Mark’s. I think that says it all. What is it that you find most objectionable about The Gap?

D: I don’t actually object to The Gap, but I’m interested and concerned with the omnipresence of The Gap, and how invisible they are. Even though they’re everywhere, and you always see the stores, there’s kind of an invisibility to The Gap. You can wear The Gap without really noticing you’re wearing it. I’m not really against what they’re doing. I think it’s part of the development of a sort of total, end-all Capitalism. And I think a lot of companies are modeling their corporate structure after The Gap—their display techniques, the language they use with employees. I think the most interesting thing about The Gap is that fashion is usually used as fantasy to transform you. But The Gap promises not to transform you. That what they’re going to do is let you shine through.

GR: Do you own some Gap clothes?

D: Oh yeah. Everybody. There would be times when we would be in meetings, discussing this stuff, and we’d look around, and everyone would have some fucking thing from The Gap on.*

1970, a 1997 exhibition at A.F.A., featured video sculpture with artist interviews about the year, 1970, in which Alex Katz said, “There’s a glitz on top, but it’s a depressed condition underneath,” and Vito Acconci stated, “I still had some kind of belief in doing art. I have absolutely none now.”

*from Grand Royal Magazine Issue 1

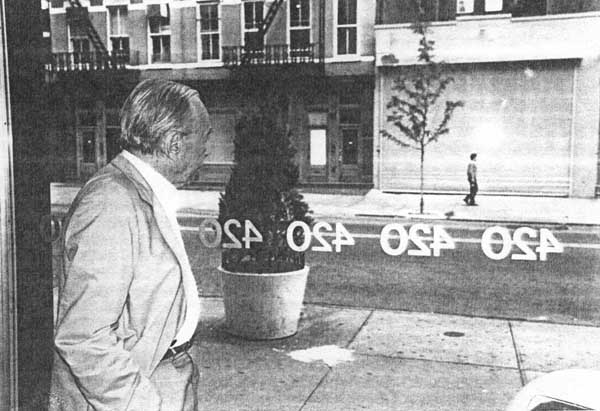

SoHo So Long

Art Club 2000, American Fine Arts Co., New York 1996,

Commingle

Art Club 2000, American Fine Arts Co., New York 1993

1970

Art Club 2000, American Fine Arts Co., New York 1997

Art Club 2000, 1999,

American Fine Arts Co.,

New York 1999

Afterword

For those of you familiar with American Fine Arts, Co., it is my sincere

hope that this project has served as a fond look back at previous activity

by a selection of AFA artists. For the uninitiated, hopefully you have

gained some insight into the legacy of a great gallery. I won't try to

attempt to list the names of people I wish I could have included, it would

easily take up the entire page.

I met Colin de Land when he came to an exhibition opening for the artist

Bob Braine at a gallery space I owned back in 1999, I was floored by his

receptiveness towards my program at the time. There are only three art

dealers I've gotten to know over the past few years that have compelled

me to continue curating, Colin was instrumental in shaping my approach

and appreciation of contemporary art.

The idea for this project came about when American Fine Arts Co. was relocating

from 22 Wooster Street to West 22nd Street (Pat Hearn Art Gallery aka.

PHAG.) in 2002. For the purposes of this editorial, I stayed close to

artists and exhibitions I was already familiar with. For some, a truly

representativehistory of American Fine Arts would highlight the “golden

era” of the late eighties/early nineties when the gallery exhibited:

Jessica Diamond, Cady Noland, & Jessica Stockholder to name a few.

Others may have memories reaching back to the mid-eighties when Russell

Joseph Buckingham, Ford Crull, Suzanne Mallouk, & Todd Anglund exhibited

with Colin in the East Village at Vox Populi (for a period of a year and

a half, when the gallery was in the East Village, AFA operated as Vox

Populi in tandem with kindred galleries with the novelty names at the

time such as: Civilian Warfare, New Math, Nature Morte, Piezo Electric

& International with Monument, the gallery reverted to its original

name in 1986). For a more comprehensive gallery “history”, I

would go back as early as 1980 to the time Colin opened the first American

Fine Arts Co. in a basement at 29 Clinton Street (The title of this project

If Culture Means Anything was the name of the first exhibition at

29 Clinton Street). Although material from over the past twenty years

is out there, going back that far would not only require access to a large

AFA storage facility which holds older documentation, but a more in depth

exchange with the large extended family that Colin de Land cultivated

over the past twenty years. Much of the galleries own early documentation

was lost in a massive flood in the basement of 40 Wooster Street, prior

to the galleries move to 22 Wooster Street.

The fall season at American Fine Arts, Co. at PHAG. promises to be as

interesting as years past beginning with a solo exhibition by J. St. Bernard,

which will be followed by solo rxhibitions by Tom Burr & Moyra Davey.

A special thanks to Daniel McDonald, Lizzi Bougatsos, Taka Imamura, John

McCord, Gareth James, Christopher Sperandio, Frank Schroeder, & Nicole

Stotzer at Parkett, Publishers for their assistance with this editorial.

James Fuentes, 2003

-- ths was first published in zingmagazine 19 --