|

.

|

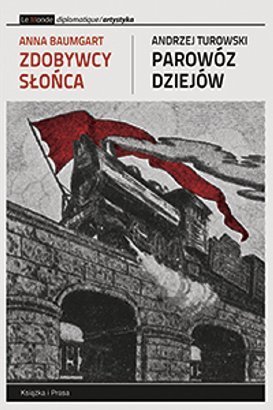

"Revolutionen sind die Lokomotiven der Geschichte", schrieb Karl Marx. „Entweder wird die Lokomotive mit Volldampf den geschichtlichen Anstieg bis zum äußersten Punkt vorangetrieben", schreibt Rosa Luxemburg, "oder sie rollt durch die eigene Schwerkraft wieder in die Ausgangsstellung zurück und reißt diejenigen, die sie auf halbem Wege mit ihren schwachen Kräften aufhalten wollen, rettungslos in den Abgrund“. Auch in der Sowjetunion wurde das Bild der Lokomotive der Geschichte benutzt, z.B. von Lenin. In der Sowjetunion werden von 1919 bis 1928 zur Agitation und Aufklärung der Landbevölkerung Agitationszüge eingesetzt: In ihnen gibt es u.a. Kino, Bibliothek und Theater. Die Avantgarde der Künstler beteiligt sich an der Gestaltung der Züge und der Programmatik. Eine besondere "Lokomotive der Geschichte" soll 1921 Kurs auf Warschau und Berlin nehmen und dort die revolutionären Bewegungen unterstützen. Von Malevich verfolgt, der dort einige Kunstwerke abgegeben hat, steht der Zug in Warschau und Berlin, wird aber nie geöffnet. Er explodiert 1928 auf einem polnischen Abstellgleis. Die Geschichte erzählen der Kunsthistoriker Andrzej Turowksi und die Künstlerin Anna Baumgart in ihrem gemeinsamen Projekt "Parowoz Dziejow" The Locomotive of History, 2012. In march 1919, Lenin decided to relaunch the Communist International (known as Comintern). Propaganda and art entered a new relationship: bolshevik politicians, proletarian artists (Proletkult) and the artists of the avant-garde crossed their paths. The avant-garde wanted to establish the Red International of Creative Artists (RICA) to accelerate world revolution. "It won't be possible to avert a world crisis using economic and political methods alone. Art is not a social luxury, but a paradigm of continous movement forward and thus it is the great energy of the revolution." Lunatcharsky, people's commissar for education at Narkompros and head of visual arts department, said: "The communist party must arm itself with the weapon of art and use it as a pillar of propaganda". Art would become a means of "communist truth". The first congress of Proletkult in 1918 was about collective visual arts to propagandize social communism. Malevich and other avant-garde artists spoke also about freedom of creativity and museums as places to educate. The most important artistic propaganda projects were the trains: "Continually on the move like living pictures, they made their way to different corners of Russia, and like a "biblia pauperum" served the aims of political persuasion. Covered with large slogans, simple forms and splashes of colour, they attracted attention wherever they went." Some wagons went to the front and agitated the triumph of the red army, others propagated collectivization. Constructivist and suprematist artists worked on the design of the trains. In 1919, Malevich was chief of the department of visual arts and sending trains with avant-garde art to many parts of Russia, together with Wladyslaw Strzeminski. He saw a clear link between world revolution and art. The idea to send a train to support the revolts in Germany came and was approved. It was called Red World, later Locomotive of History. But first, the train came to Smolensk where the western front was. Unovis artists joined the group. El Lisitzky said: We are going to the west not with art but with communism. Revolutionary art should be disseminated beyond the borders of nations. At the same time, the group had the project to build museums of the future in Russia and Berlin. The train should carry its first exhibition. Proletkult congress in 1920: Art organizes social experience. It is thus a powerful instrument for organizing collective forces. "Unovis is a creative collective. In our studios, new forms of existence are built and projects become living entities." (142) In 1920, the wagon should go as part of an armoured train via Warshaw to Berlin. But first, in 1921, it was El Lisitzky who went to Berlin, having studied in Germany and also was the member of the group who had via the jewish cultural network Kultur Lige most contacts in Poland, Russia and Germany. He took part in the exhibition of russian art in Berlin in 1922. The train parted, painted grey, from Smolensk to Warshaw, where it was boycotted by the polish for hating the russians and especially the "popular-semitic" avant-garde movements. Artists wanted to open it, but soviet diplomats denied. In march 1924, it set off to Berlin. Political powers in Soviet Union changed, Narkompros lost power and Cheka was replaced by GPU. The Bolsheviks began to criticise the works of the avant-garde. Polish avant-garde orientated to the west: Collaboration with Novembergruppe, Gruppe progressiver Künstler, Veshch etc. - Artistic Internationalism came up again. Malevich decides to look for the train and parts from Leningrad in 1927, risking his residency permit because he left without a permit. Malevich hangs out with Gruppe progressiver Künstler, Novembergruppe, Stanislaw Kubicki, and architect Hugo Häring, who organized Malevichs participation in Große Berliner Ausstellung in may 1927. From his diplomat friend Gustav von Riesen, Malevich knows that the train arrived in 1925, but was under surveillance by the security forces. As it was sealed as shipment for the russian embassy, Germany couldn't open it without risking a diplomatic row. They wanted to send the train back to Poland. Warshaw's soviet diplomat Voykov opposed and insisted on handing the train out in Berlin, and was killed. Malevich was called back a few days before that to Russia and left a lot of works behind. He was imprisoned for espionage. The train was sent back to Poland, to Koluszki, where Sztremisnski went for work. He knew by chance about it and searched for it, with no success. One morning, the train exploded. The locomotive of history became a "political spectre". "The locomotive of history was the lost truth of future history which once drifted among the imaginary islands of modern utopia." (All quotes: Andrzej Turowksi, The Locomotive of History, 2011)     |