|

Re Contruction Comparative Studies . . . . . . Hilfe |

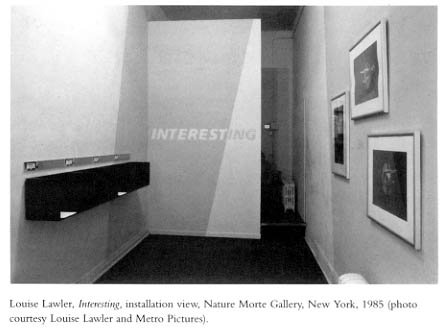

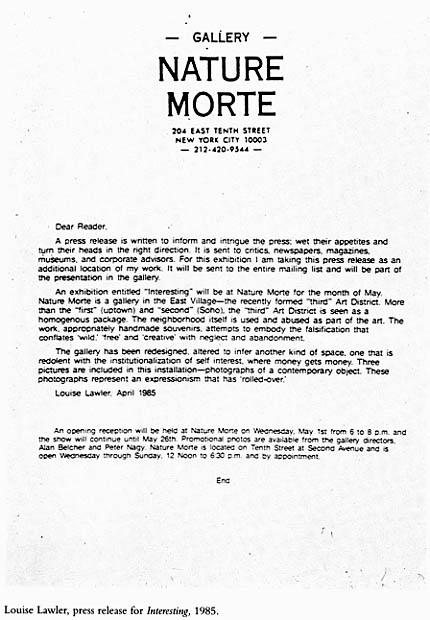

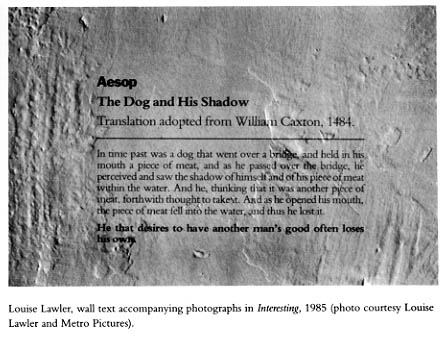

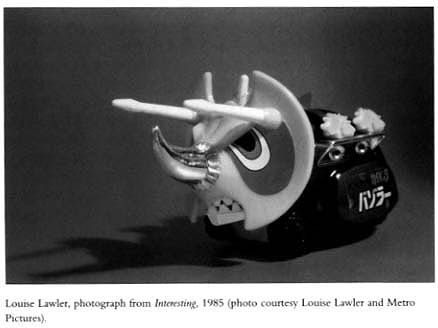

Louise Lawler INTERSTING at Nature Morte 1985 Louise Lawler, by contrast, belongs to that group of artists whose work demonstrates that the identity of art is socially produced, inseparable from the conditions of its existence. To illuminate the contingency of aesthetic meaning, she calls attention to modes of artistic display, using the context of an exhibition as part of the material of her work. She generally locates her projects in the array of equipment used by art institutions to present objects as art—gallery invitations, installation photographs, press releases, wall labels. She thus employs elements of art's framing apparatus to question the institution's claim that it merely recognizes and displays, rather than constitutes, aesthetic values. Appropriating the institutional apparatus as both target and weapon, Lawler's gallery installations, as one critic succinctly put it, concentrate on presenting the gallery "rather than being passively presented by it."  When Lawler presented an East Village gallery, she altered it "to infer," as she wrote in the show's press release, "another kind of space, one that is redolent with the institutionalization of self-interest, where money gets money." Redesigning the gallery's interior so that it looked like a bank lobby, she painted the walls with a commercial supergraphic and stenciled the logo "Interesting" in corporate typography on the gallery's rear partition. Segmented by the edge of a diagonal green stripe that divided the partition, the word interest became the installation's leitmotif. Lawler's conversion of the space did not ingenuously equate art galleries with financial institutions, suggesting that galleries are principal actors in the Lower East Side housing market. Neither did Lawler simplistically inform her audience that galleries deal in commodities, thereby reducing the meaning of artworks to the economic circumstances of their production. She did attempt to use the gallery to intervene in the dominant production of meanings taking place within East Village galleries and other art-world institutions. While these institutions deflected attention from the role they were playing in urban social conditions, Lawler's installation addressed that role, focusing first on the gallery's interior and then infiltrating it with allusions to the real-estate, housing, and art markets, which, though conventionally relegated to the gallery's "outside," were actually the conditions of its existence. The word interest—casting doubt on the notion of disinterested aesthetic contemplation—resonated in the redesigned space with implications of self-interest and references to the financial interests served by the East Village art scene. It hinted at the acquiescence of that scene in the activities of still more powerful economic interests.  With trenchant humor, Lawler also commented on the relation between contemporary urban spatial arrangements and the regressive ideas about aesthetic space embodied in neoexpressionism. On one side of the gallery she installed a shelf that resembled the counters where bank customers prepare transactions. Instead of deposit and withdrawal slips, however, this counter offered press releases referring to the exhibition's urban context and to what Lawler called the art scene's "use and abuse" of the Lower East Side neighborhood. Across the room hung three Cibachrome photographs accompanied by a wall text with the standard format and typography of museum or gallery labels. Instead of providing a pedigree for an artwork, however, this label related an Aesop's fable. The fable, concerning responsibility and the wages of greed, narrates the adventures of a dog who carries a piece of meat in his mouth. Crossing a bridge, the dog is tricked by his reflection in the water below and, opening his mouth to snatch the meat that he thinks he sees there, drops his food into the water. Confused by an illusory image of himself, he loses his grip on reality.  Like the animals in Aesop's fable, the inanimate object in Lawler's photographs can also be used to tell a tale. This story, too, alludes to the consequences of illusions about the self. The object is drastically enlarged and dramatically lit against rich, deeply saturated monochromatic backgrounds—red, green, blue. The photographs were matted and framed like valuable art photography. But the photographed object itself is far from a precious commodity. It is, rather, an inexpensive Japanese toy called the Gaiking Bazoler. Mechanistic and aggressive little creatures, Gaiking Bazolers wear exaggerated, cartoonlike facial expressions that can be altered by attaching different noses selected from a supply of standardized parts. Different facets of their temperaments can also be emphasized, as Lawler did in her photographs, by viewing the toys from different angles.  Lawler had photographed the Gaiking Bazolers before her East Village show. But since her work argues against the contention that immutable meanings reside inside self-contained artworks, she continually reuses pictures in new contexts that inevitably change their meanings. In the Interesting installation, the sham ferocity of the commercial novelties, flaunting their "individual" expressions, functioned as spoofs of East Village art, a commodified and childish expressionism that strained to produce startling effects as it repeated habitual and outworn gestures. Lawler's photographic blowups—and her overblown handling of the Gaiking Bazolers— combined the seductive techniques of commercial photography with methods of artistic presentation that create an aura of sanctity around art objects. Her treatment mimicked the hyperbolic manner in which pseudo-expressionist products and the East Village art scene as a whole were artificially inflated by the marketplace and propped up by an art discourse that espoused transcendent values while capitulating to the conditions of the culture industry.87 The photographs represented, in Lawler's words, an "expressionism that has 'rolled-over.'"  Lawler's parodic reenactment of this inflationary operation and her deployment of the Gaiking Bazolers in the East Village installation emphatically deflated the pretensions of such work. Interesting also punctured the widespread illusion that recycled urban expressionism confronts the harsh realities of "the urban situation." For, as Lawler's (de)fetishized objects suggested, in the context of devastation on New York's Lower East Side, solipsistic exercises in bombastic self-expression—products of "the urban personality"—gloss over the sources of urban brutality: the politics of space. They could only serve those powerful interests whose presence in our cities we have every reason to fear. From Rosalyn Deutsche "Representing Berlin" |